Michigan Sentencing Guidelines

For felony cases, Michigan uses an indeterminate sentencing system. This means that at sentencing, the judge will set both a minimum sentence and a maximum sentence. Your minimum sentence establishes the date at which you will be eligible for parole, also called your earliest release date or ERD. The Parole Board determines whether you will be released after you’ve served your minimum sentence. Hypothetically, the Board could continually deny you parole (commonly referred to as a “flop”) until you’ve served your maximum sentence. Once you’ve served your maximum sentence, though, you must be released. (As a practical matter, most prisoners are released on parole close to their ERD.)

Here’s an example. Say you were sentenced to 10 to 15 years in prison. After 10 years, the Parole Board has jurisdiction in your case and can decide to parole you. But even if they keep denying you parole, after 15 years, you must be released.

So how does the judge set the minimum and maximum terms? The maximum sentence is usually set by statute, and the judge therefore has no discretion to alter it. For example, first-degree home invasion is punishable by up to 20 years in prison under MCL 750.110a. So when the judge sentences you for first-degree home invasion, he or she has to impose a maximum sentence of 20 years.

The minimum sentence gives judges a lot more wiggle room. In most cases, the judge sets the minimum sentence by reference to the Michigan Sentencing Guidelines, often referred to in court simply as “the guidelines.” In a nutshell, the guidelines grade each defendant based on his or her prior record and the circumstances of the crime. The more serious the offense and the more prior offenses the person has, the longer the sentence they’re going to receive. The idea behind the guidelines is to bring uniformity to sentences throughout the state so that two equally situated defendants should receive the same sentence regardless of whether their crime was committed in Detroit or Escanaba. (In practice, it’s far from clear that the guidelines are accomplishing their stated goal.)

Let’s take a closer look.

How the guidelines work

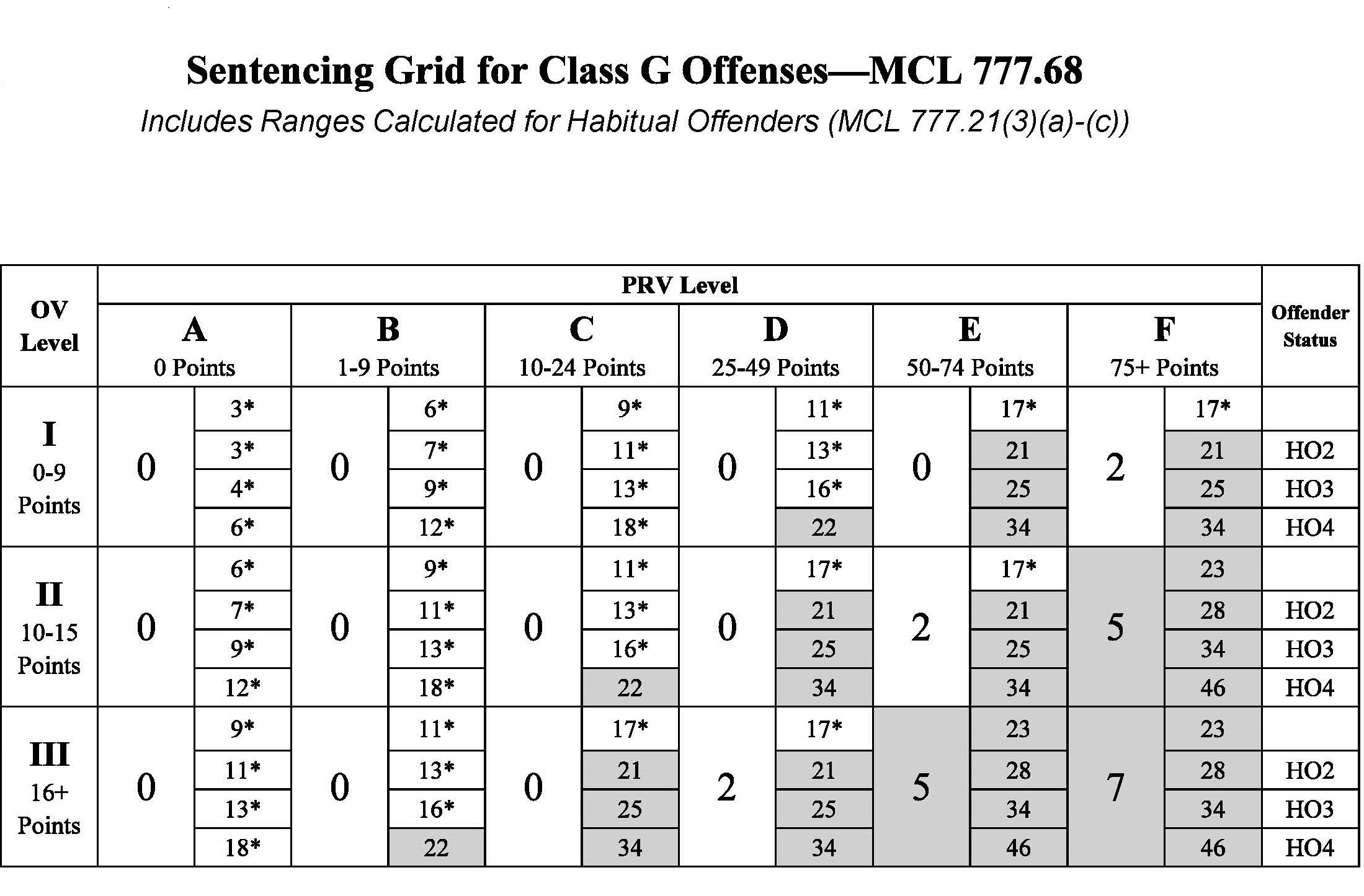

First, the guidelines divide most felonies among eight different “class” levels, ranging from A (the most serious) to H (the least serious). (There’s also a separate level exclusively for second-degree murder.) So, for example, first-degree criminal sexual conduct and armed robbery are Class A offenses while resisting or obstructing a police officer (R&O) and failing to register as a sex offender are Class G offenses.

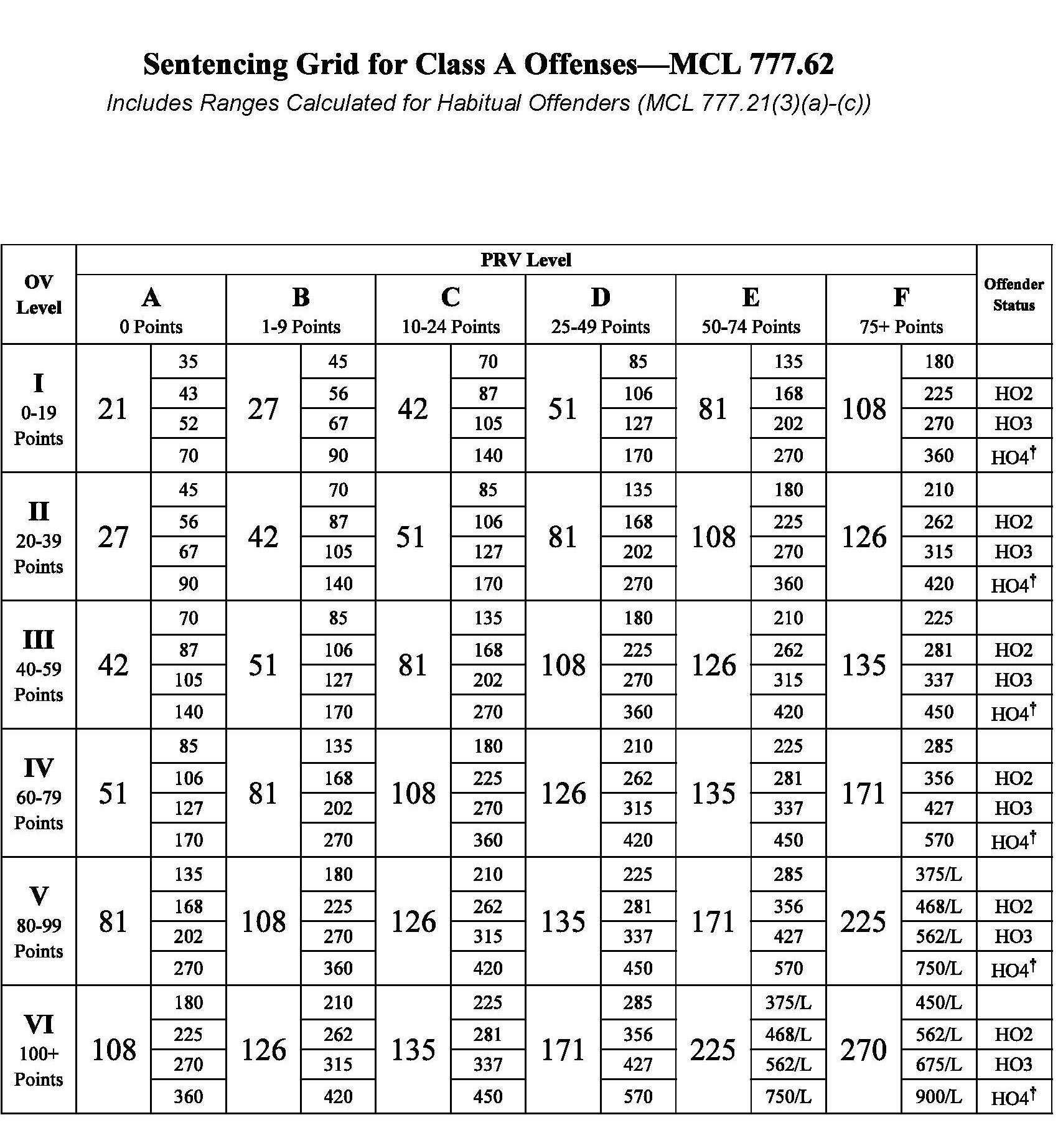

Here’s the Class A grid:

And here’s the Class G grid:

As you can see, where a defendant falls on any particular grid depends on their “OV Level” and their “PRV Level.” OV stands for offense variable and PRV stands for prior record variable.

Let’s start with the PRVs. As the name implies, they address your prior record. For example, here’s PRV 1, which addresses prior high severity felony convictions:

Other PRVs address low severity felony convictions, prior misdemeanors, and subsequent or concurrent felony convictions.

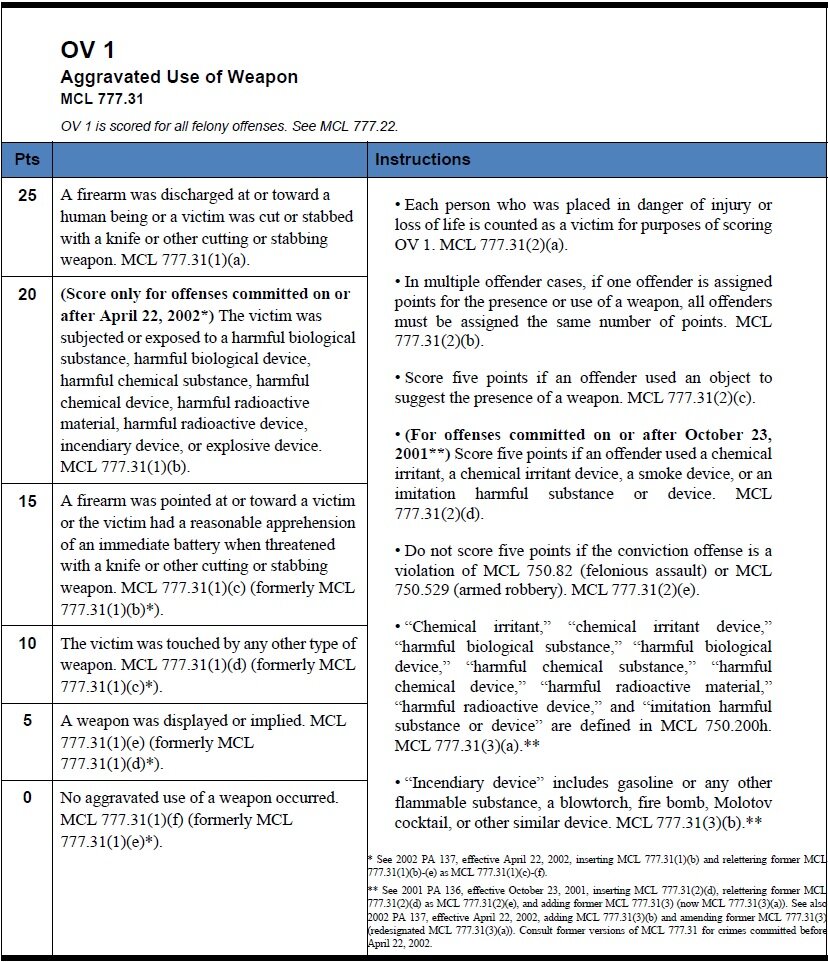

Moving on, OVs generally add points to account for the egregiousness of the crime. For example, here’s OV 1, which addresses the aggravated use of a weapon:

Other OVs address psychological injury to the victim, aggravated physical abuse, and the number of victims to the crime.

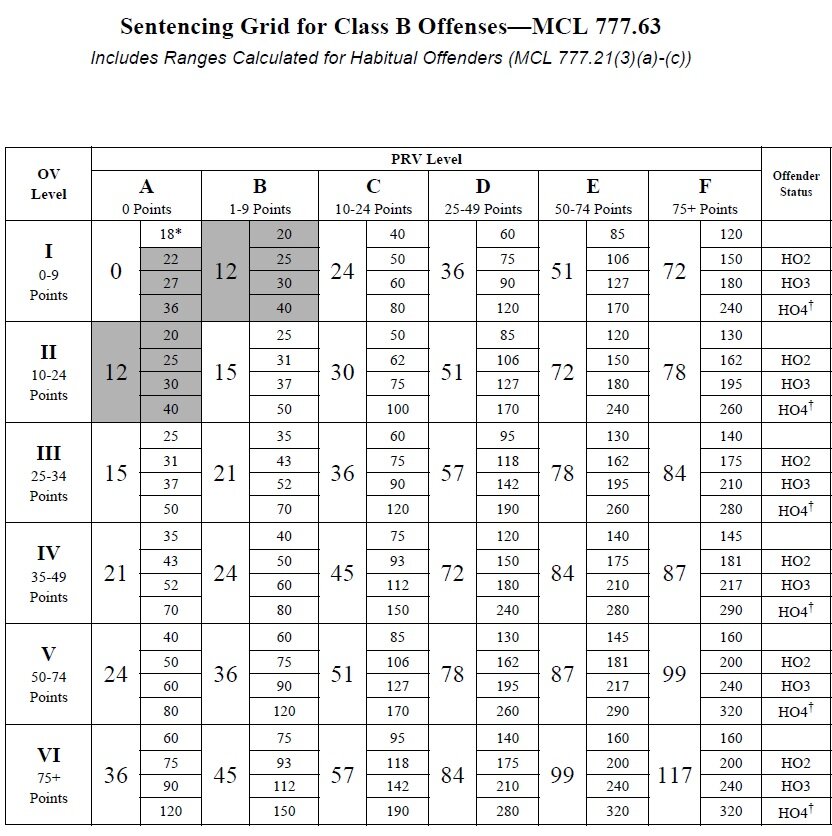

So once you have your total OV and PRV score, you reference the grid to see where you fall. Take a look at the grid for Class B offenses:

Say you were convicted of third-degree criminal sexual conduct, a Class B offense which carries a 15-year maximum sentence. Assume your total PRV score is 15 and your total OV score is 40. This puts you at PRV level C and OV level IV, so your guidelines range for your minimum sentence would be 45 to 75 months. (The numbers under the 75 only apply if you’ve been “habitualized” as a repeat offender.) Ordinarily, then, the judge would pick a number between 45 and 75 as your minimum sentence. Let’s say the judge picks 48 months, which equals 4 years. Therefore, you would be sentenced to serve a minimum sentence of 4 years and a maximum sentence of 15 years, or “4 to 15.” Make sense?

Can the judge go over (or under) my guidelines range?

The short answer is yes, the judge can pick a number that’s either above or below your minimum sentence range. This is referred to as a departure, and it can be upward or downward. (In practice, upward departures are much more common than downward departures.) Previously, judges’ ability to depart was tightly constrained. But in July 2015, the Michigan Supreme Court issued a decision in People v Lockridge, which made the guidelines advisory, i.e. nonbinding. Under Lockridge, judges must still correctly score and refer to the guidelines, but they’re no longer constrained to follow them, or at least not to the degree they were before July 2015.

The law in this area is still developing in the wake of Lockridge, but there have recently been some positive developments for criminal defendants. Several decisions from the Court of Appeals have stated that even though the guidelines are only advisory, a judge cannot depart willy nilly—the judge has to have both a good reason for a departure and a good reason for the extent of the departure. I recently won a resentencing for a client in the Court of Appeals based on an argument that the judge did not adequately justify the extent of the departure he imposed.

Long story short, though, there’s almost always going to be a possibility that the judge will exceed your guidelines range. But in the right case, you can also pursue a downward departure more easily.

What if your guidelines are wrong?

So what if your guidelines were incorrectly scored? Will you be able to get your sentenced reduced? It depends.

If the errors in your sentencing guidelines mean that you were sentenced under an incorrect range, you should be able to get resentencing, a new sentencing hearing. For example, take a look at the Class C grid:

Imagine that your PRV score was 10 and your OV score was 65, so you’re at PRV Level C and OV Level V, leaving you with a range of 36 to 71. (Again, ignore the 88, 106, and 142 unless you’ve been “habitualized” as a repeat offender.) At sentencing, the judge sentences you to the bottom of the guidelines, 36 months, which equals 3 years.

Let’s say that after sentencing you hire me. I review the guidelines and discover that although your PRV score is correct, your OV score is not. Really, your OV score should have been 55. Unfortunately, because this still leaves you in OV Level V with the same 36-to-71 range, you will not be entitled to resentencing, even though your guidelines were technically wrong. But let’s say I discover that your OV score really should have been 45. This would put you in OV Level IV, which has a range of 29 to 57. Because the range has now changed, you will be entitled to resentencing.

The sentencing guidelines can be extraordinarily complicated. Judges, prosecutors, and trial attorneys are busy, and they don’t always pay close attention. I would say that it’s quite common for me to find guidelines errors when I review cases on appeal. And often the errors are substantial enough that my client will be entitled to resentencing. Overall, guidelines errors are probably the easiest way to get relief for criminal defendants on appeal.

Resentencing does not mean reduction

It’s important to point out that just because you’re entitled to resentencing doesn’t mean that the judge will necessarily reduce your sentence. Take the preceding example. The client started off with a 36-to-71 range, the judge initially sentenced him to 36 months, but the guidelines actually should have been 29 to 57. Although the judge would be required to resentence the defendant (to hold a new sentencing hearing), the judge would not be required to reduce the defendant’s sentence at that hearing. In fact, it’s not necessarily unusual for a judge to impose the exact same sentence at resentencing even though the guidelines have changed. Still, many judges often feel constrained to reduce the sentence once the guidelines range has been lowered. Whether you can get a reduction largely depends on the judge and the specifics of your case.

Can the judge increase my sentence at resentencing?

Rarely, but sometimes. Generally speaking, a judge can only increase your sentence if new information about you or your case is brought to light at resentencing. The classic example is the client who has been racking up misconduct tickets in prison. The judge can consider those tickets and use them as a basis for increasing your sentence. That’s why I always advise all my clients to keep on the straight and narrow while their case is on appeal. A bad prison record can often sink what could otherwise be a successful resentencing.

This is a very, very brief overview of the Michigan Sentencing Guidelines. The guidelines can be extremely complicated, and there are many factors that I did not cover in this article. Here’s a link to the sentencing guidelines manual put out by the State of Michigan, which is comprehensive.

For more information about your particular case, consult an experienced criminal appeals and postconviction attorney.